My experience in Florence, Italy, transformed my appreciation of the challenges and importance of drawing the human figure, inspiring my personal growth and resilience. I was there for 7 weeks as part of the Florence Academy of Arts Drawing and Painting Intensive. The class was a condensed version of the 2-year course of study, covering the same topics but drastically shortened. Figure drawing was a component of the curriculum, and one that was both challenging and transformative.

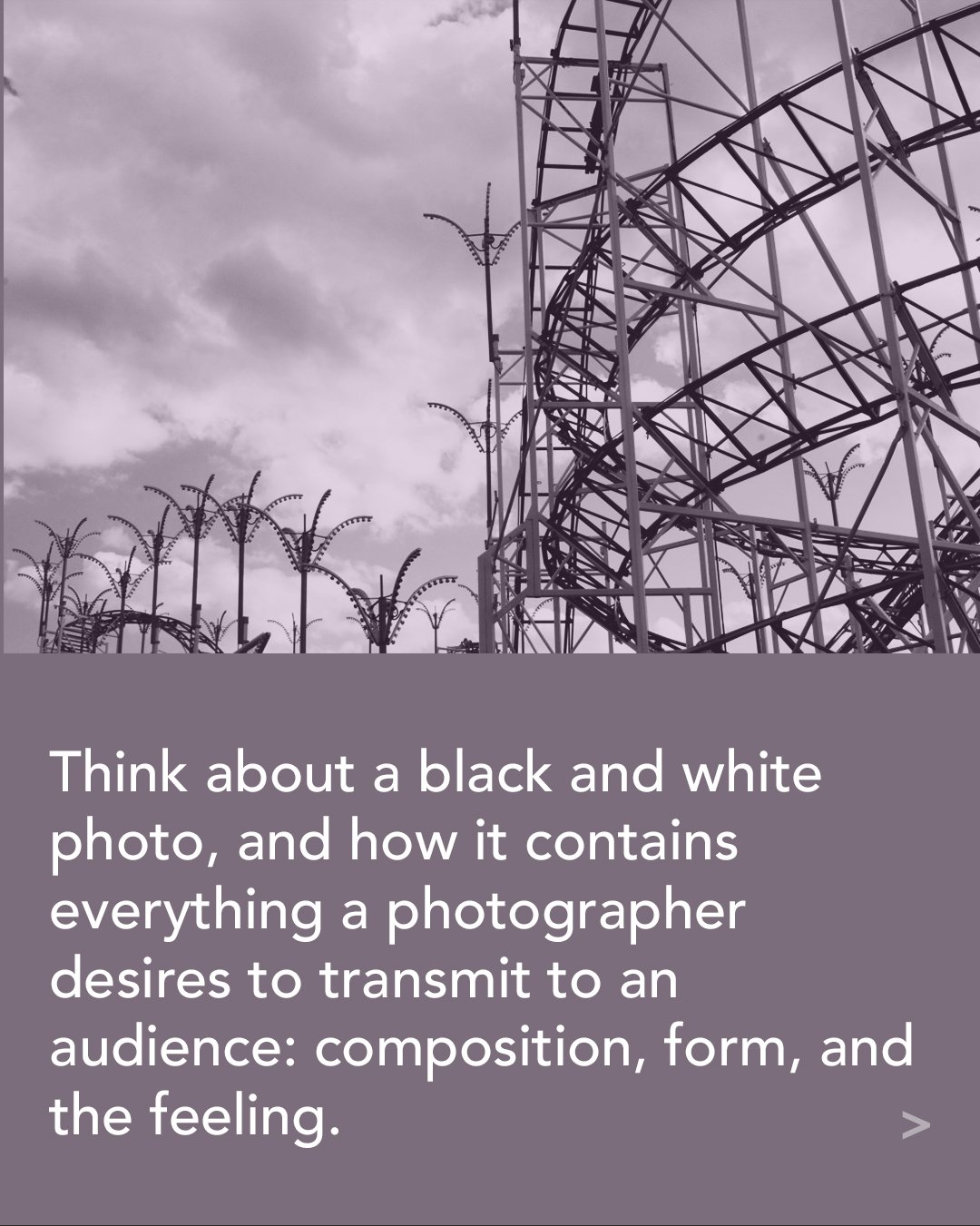

Figure drawing of a long 3+ hour pose is a different set of challenges that doing a series of short, say 15 min poses

The class ran for six weeks, from 9 to 4 pm Monday through Thursday. Friday was a free day, and we were encouraged to explore the city's many museums. There were 12 adult students from around the world with varied backgrounds. The whole program was intense and very guided. This was not like the classes or workshops I had experienced in Boston/Cambridge, where students could pick their subject or start creating art, and the instructor would walk by to offer additional feedback and a little guidance.

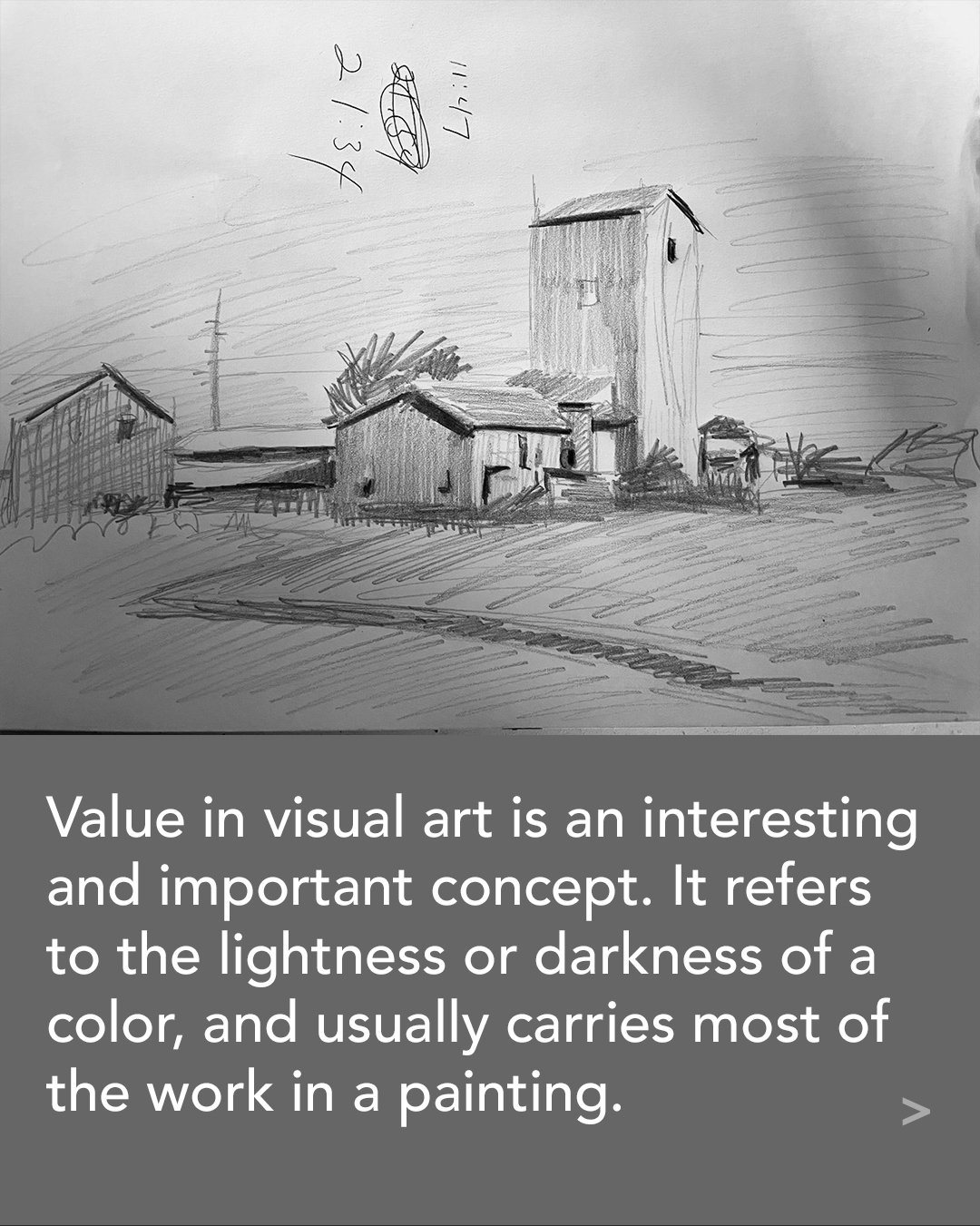

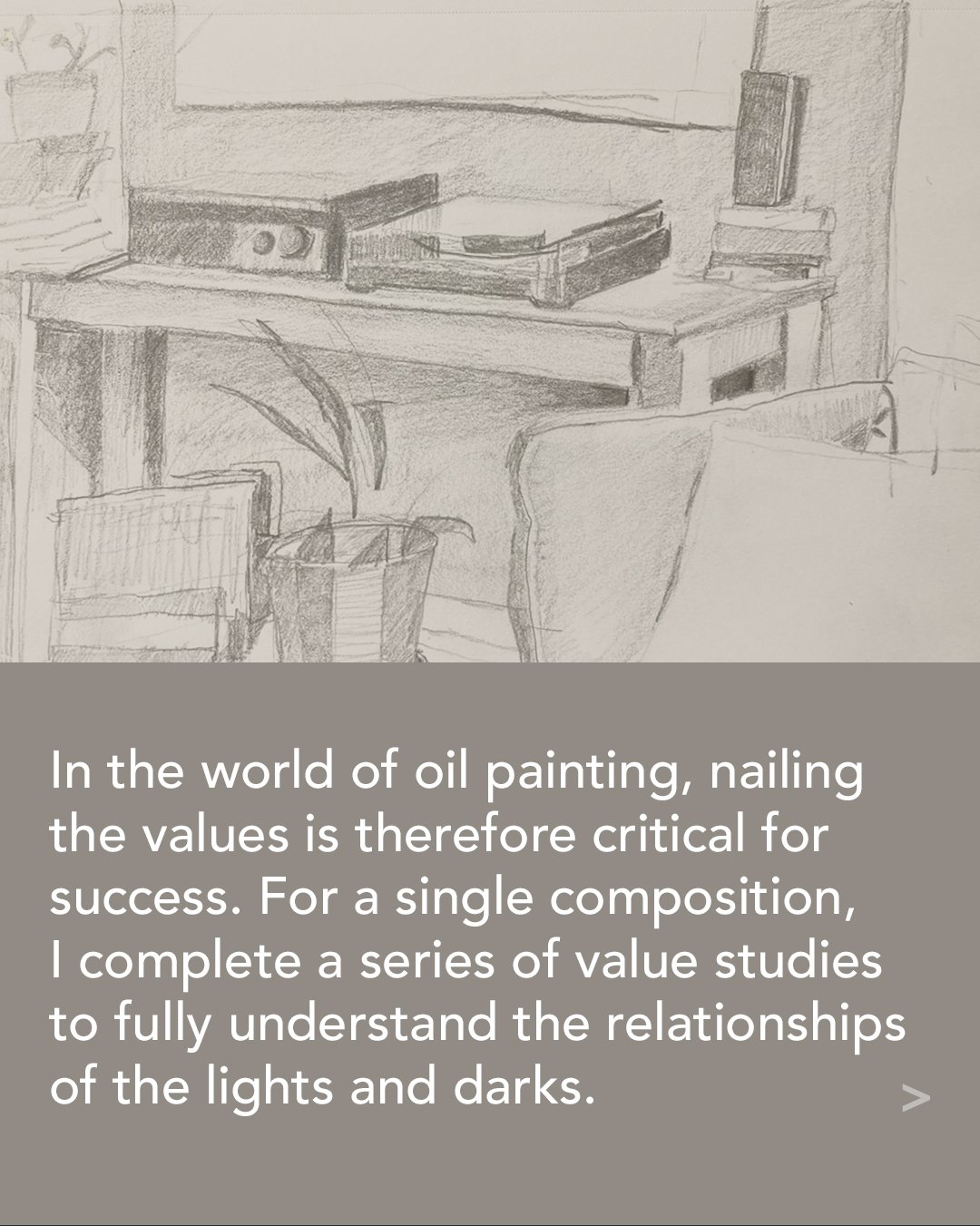

Replicating classic anatomical drawings was a great way to start this intensiove class.

This was more like what I envision the military to be. We were provided specific subjects to paint. We were told how to place the subject relative to our drawing or painting surface. We put masking tape on the floor to mark the easel and subject so that if we needed to come back the next day, we would be sure everything was in the same place.

We used masking tape to mark on the floor where our subject and easel were to ensure everthing was always the same positioning.

We were instructed on how to look at an object, what to look for in a subject, how to measure an object's dimensions, and how to estimate its proportions. We were guided on how to start a painting and given a heads-up on things to avoid. It was incredible, and I enjoyed it immensely. However, it was truly like drinking out of a fire hose. There was so much new information and skills in such a short time, and I learned that trial and error is a vital part of mastering art. Embracing mistakes and persistence helped me improve.

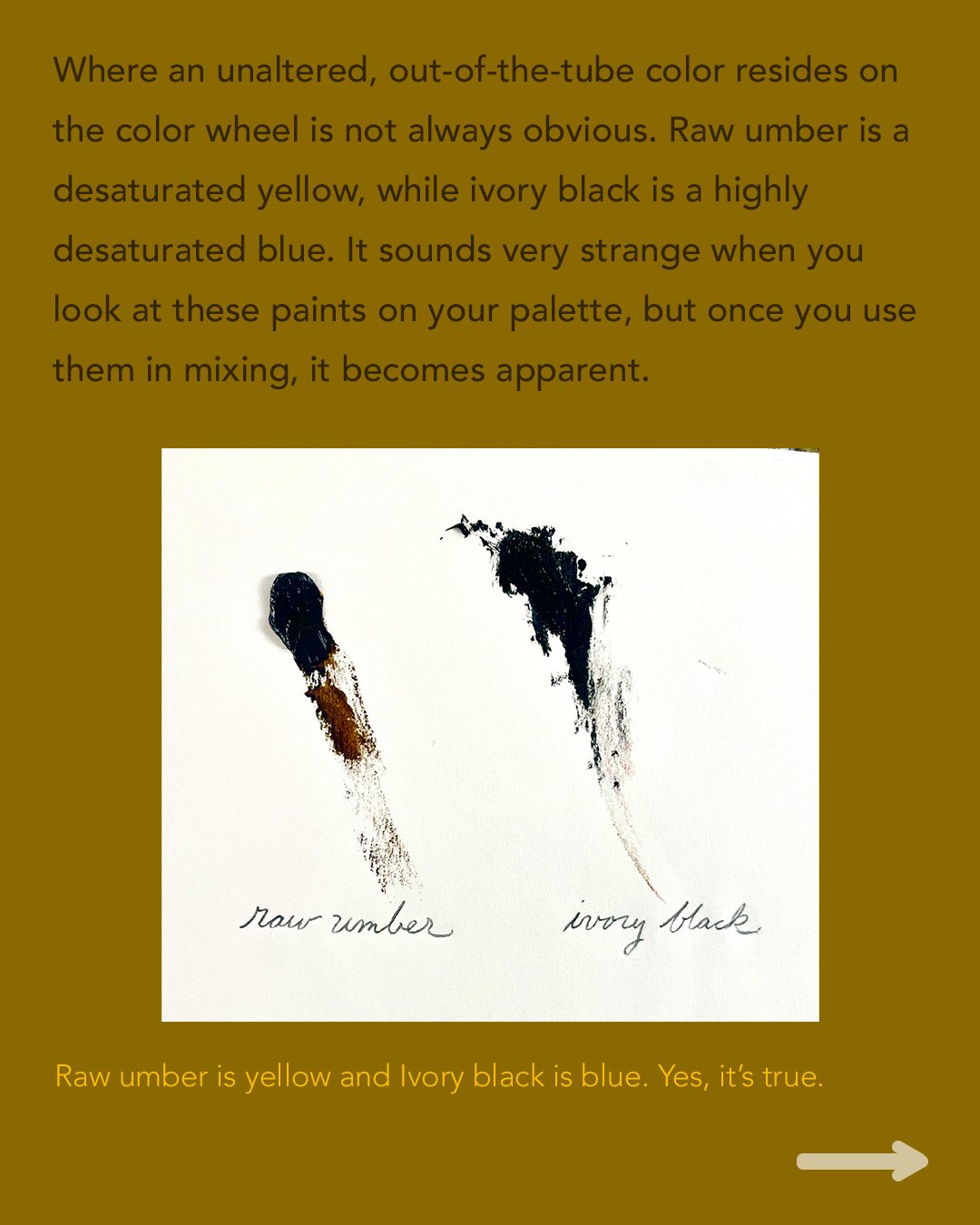

We started the course by copying classic drawings of anatomical elements, such as an arm or a hand. The expectation was to replicate the drawing exactly, including the line weight and form. Initially, it was not a very creative experience but rather like a series of technical drills. I recall having drinks with all the fellow students after class one evening, and we shared how the class experience was different from what we all expected. Everyone was very appreciative of the instruction and the learning experience. Still, we joked that our friends at home would be expecting to see lots of elaborate, colorful paintings we would have created after 2 weeks in Italy, when all we had made were a few high-quality drawings of hands and arms. It was very humorous. It really bonded us as a group, as we were experiencing something very special and unique to us, something no one but us would have understood.

After more elaborate drawing experiences, each lasting at least 1/2 a day on a single subject, we moved on to painting. Painting was started very simply, four colors with the simplest still life, a single pear placed in a black box to create the background to make the object really pop.

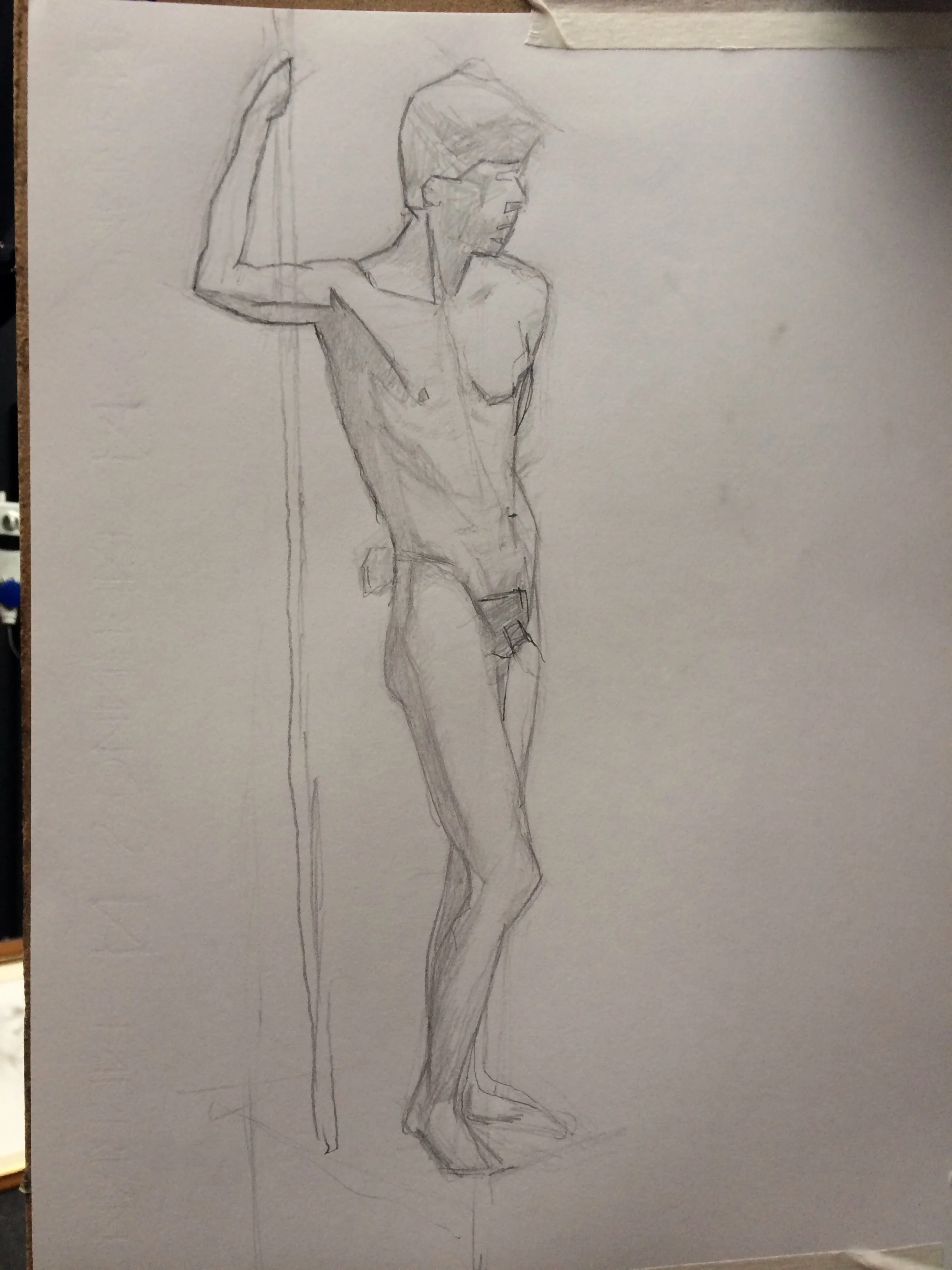

The pinnacle of the class was figure drawing, closer to the end, as it really relied on the skills developed in the previous weeks. I actually had two different experiences with figure drawing in Italy. One was in a very guided class. The other was more open and free, at a drop-in figure drawing session open to the public on Thursday evenings at our school. This was quite interesting as I was able to be exposed to other artists beyond those in my class, some of whom were highly experienced. In these open studios, there was no guidance offered, as there was no instructor. There was a minimal fee, and attendees would bring their own drawing or painting tools. As I recall, almost all of the students were drawing.

Even a non-artist can tell if the alignment of the human form is off even in the slightest

The model had a handler, someone who would deal with the individual leading the session, handle the business side of things, and certainly book the gig. I found it fascinating that being a life model could be a real job in Florence, Italy. The model would work with the open studio lead to set up the pose. The model would be on a slightly raised platform in the front of the studio, with the students arrayed all around their canvases at about a 120-degree angle.

They would hold a single pose for the entire session, about 3 hours, so the pose needed to be engaging and developmentally valuable to all students, regardless of their location around the platform. There was a lot of back and forth, with the model making changes - hand on thigh? Hand on hip? Seated or standing? Leaning on a vertical rod? With the light adjusted to show good shadows, revealing the form.

Once the pose was established, the session would begin. As a beginner figure drawer, 3 to 4 hours in a single pose is a very different experience and expectation from the typical short sessions I was accustomed to. In my previous experience in Boston and Cambridge, MA, any time I participated in figure drawing sessions, they were a series of short poses, each maybe 15 minutes long, and then the model would change, and a new drawing would start. These became more of a quick sketch, attempting to capture the proportions of the figure, a challenging task in itself, and documenting the most significant differences in value. The shape of the darkest shadows, the contour of the medium values. The expectation of detail and fidelity can be low, since you only have this short period of time for the pose before moving on to a fresh pose, fresh paper, and a fresh drawing.

With a long-form pose, expectations are higher, and the approach is very different. Luckily, the Academy provided us with specific techniques in the figure drawing segment of the curriculum. They offered techniques and methods for each phase of the drawing process. Locking the key points of the figure on the surface, the top of the head, the lowest point of the figure, usually the end of a big toe pointed down, the chin, breasts, pubic area, and knees. These would all be marked on the paper first vertically and then horizontally. It is the most essential part of the drawing, and having professional guidance was helpful. However, even with the guidance, this is highly challenging.

There are aspects of figure drawing that make it so unique, powerful, and foundational to a visual artist. You do not need to be a trained art instructor to know if your drawing is not reflecting the subject accurately. As a human, it will be very apparent. This is very different from documenting a subject, such as a landscape, where it can be more forgiving. Suppose the relative distance between a tree and a barn is a bit off. In that case, it will not jump out in the same manner as if the distance between the shadow of an eye socket and a nostril is off, even in the smallest amount. You will know immediately.

This introduces a series of alerts, but knowing how to fix them is another story. Shifting one element will affect everything else. And there is also the technique of erasing and redrawing. It is a constant flowing, lively experience that is one of the most challenging mental experiences I have ever encountered. Because of the fact that you can see, process, and be aware of any errors, and that everything is completely interrelated, and you are dealing with the most fundamental parts of our brain, the human figure. We are hard-wired to process the human form.

Developing the skill to draw the human figure is one of the most profound examples of the learning process. Trial and error. Completing a project with a result you may not be thrilled with, one that has errors, but you start again and do your best. Guidance from instructors or experienced artists can be very helpful in developing techniques and approaches for various aspects of this. Still, a lot of it is just doing it. Trying and failing, and our amazing human brain will develop skills just by doing.

I often tell people that figure drawing for a visual artist is like yoga for an athlete. It is helpful and applicable to any area of visual art you participate in, as it develops foundation skills. It is something you may not master, but it is good to keep doing, staying focused, and trying to learn and improve. Figure drawing helps calibrate the accuracy of what an artist sees with what they place on the canvas, particularly in terms of proportions, form, and shape. Suppose you master how to accurately document the proportions indicated by the human form. In that case, you will be in a much better place to do so for the more forgiving bowl of fruit still life.

I am very grateful for the intensive, immersive human figure drawing experience I had in Florence, Italy. It revealed the extraordinary artistic and development opportunity this activity offers me as an artist and as an active, engaged, curious person in our physical world.