Serendipity is a happy or beneficial event that happens by chance.

If you ever meet me at a cocktail party, once we establish our locations of origin and where each of us grew up, I will often ask about your local childhood amusement park. It is a decent conversation starter; every area of the United States has one, and they are usually associated with positive memories. I have most of them cataloged, so no matter where you grew up, I can serve up this memory generator.

“Kings Dominion! I worked there 3 summers!”

“Oh my Gosh - Great Adventure! The ride where the room spins and the floor drops? I threw up on that thing! We loved that place.”

My dear friend Ditty grew up near Harrisburg, PA, and we established early on in our relationship that Knobels Grove was his childhood amusement park. I had never visited the place, but I had been hearing about it and its infamous Phoenix roller coaster for years. It was definitely on my list of places to visit, but being in a rural part of Pennsylvania, I might never get to. I was constantly peppering him with Knobels’ questions, trying to get him to share memories and details about this magical place. He put up with it but never shared much. “I don’t remember many details., Dickles, I was just a kid.”

“I know that, but did you go on kiddie rides? Did you go on adult rides? Was it a day trip?” I was looking for any bit of info.

“I guess I must have visited with all of my uncles; they took me everywhere.”

I was always left disappointed with these conversations. I had a reliable source here, but he seems unwilling to share any information. His lack of passion for Knoebles was also a letdown.

One year, Ditty invited me to travel back home to Pennsylvania with him for his annual family Christmas visit. It would be a road trip from Boston, where we lived, to Sunbury, PA. He wanted me to meet his family and see where he came from and where he grew up. Ditty and I travel well together, as we often make the 4-hour drive from Boston to Southern Vermont on a Friday afternoon to the ski house we were both part of. We enjoy each other’s company, often telling each other silly stories about various sexual exploits, and we love to sing along to music. His favorite road trip activity is what he calls “playing the Dickles,” where he aggressively pokes my legs and thighs along to the beat of the blaring music, with vocal accompaniment, which becomes a borderline tickling situation.

Ditty was in charge of the drive routes, stops, and timing. He had done this trip many times. When we unexpectedly left the highway and entered rural, winding roads earlier than I anticipated, I noticed but didn’t comment. I trusted Ditty, though something felt off since we were nowhere near his family home yet.

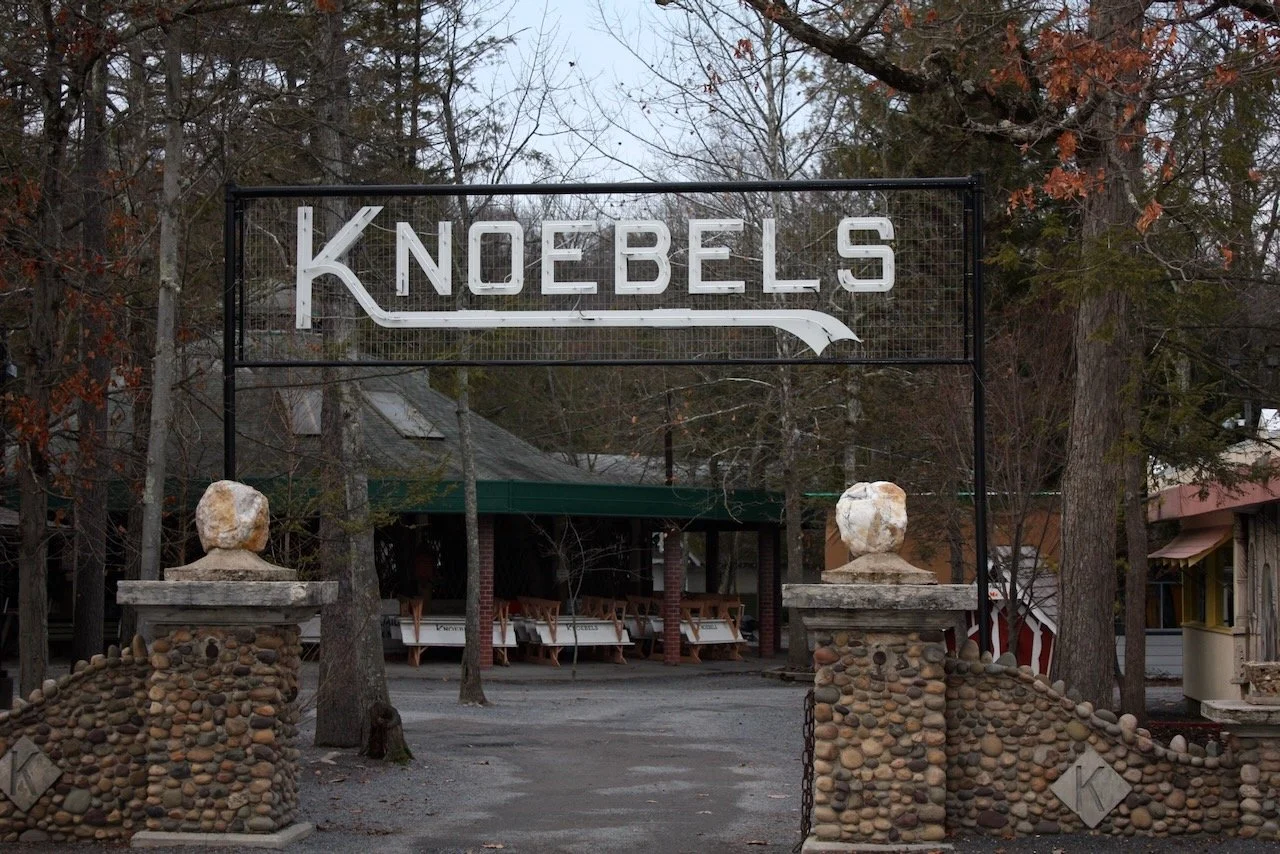

All of a sudden, there it was. Spanning across the wide two-lane road in the woods, a giant white sign overhead with colorful decorative letters:

Welcome to Knoebels

America’s finest family fun park

I was nearly speechless. “Ditty! Do you see this?? We are at Knoebels.”

How did this happen? Had we made a wrong turn? Indeed, this was not his normal route home - he would have warned me. And it would have come up on those many Knoblels grilling sessions. What was happening?

“Yes, Dickles! It is my Christmas surprise for you! It is off-season, so the park is closed, but I made a special detour so that you could see Knoebels. I know you've been talking about it for years.

We can stop and look through the fence if you want.”

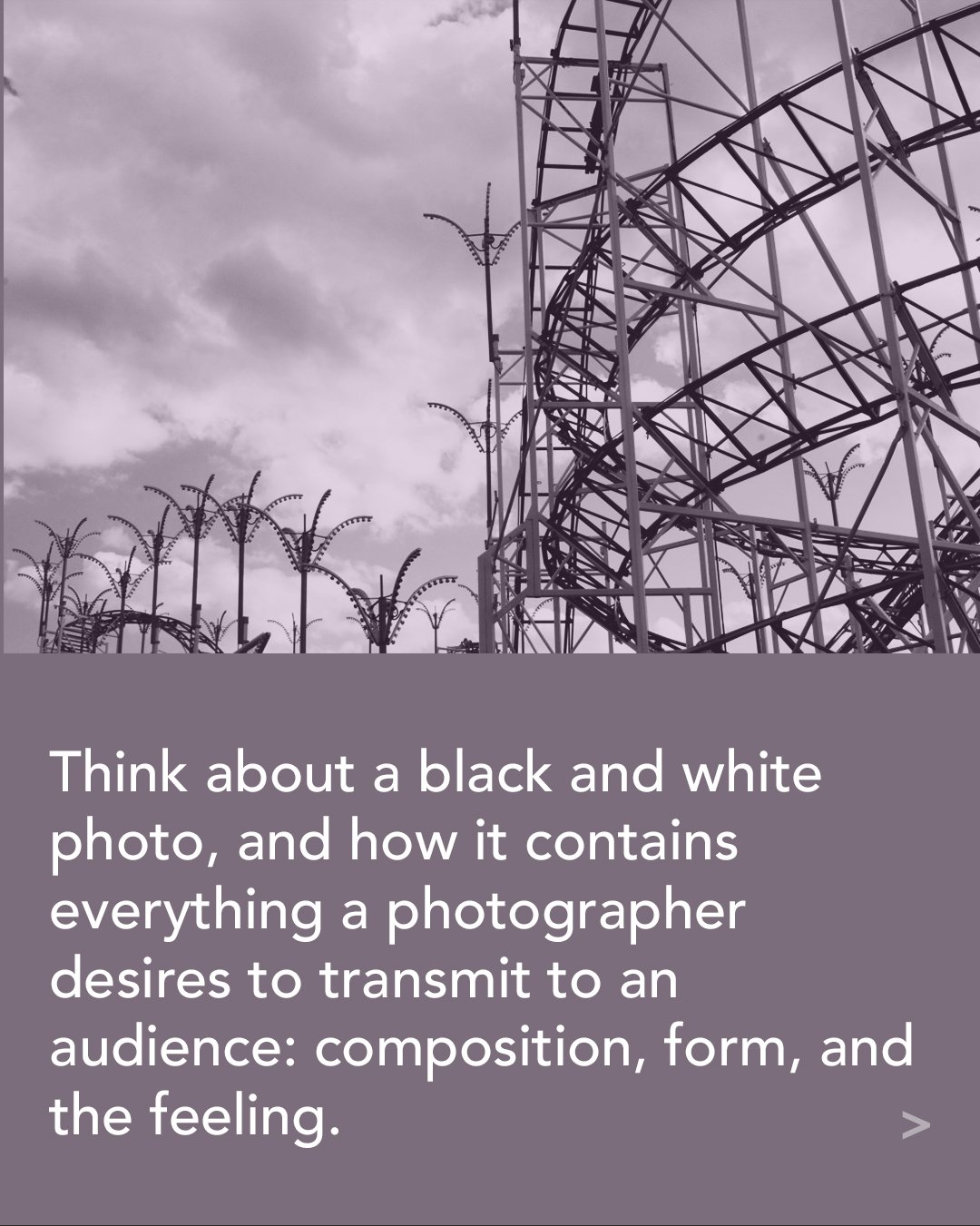

As we drove under the sign and further in, it became very clear that this was not a normal fenced-in amusement park, closed off to the public off-season. The park had no fence. The public roads run right through the park, and the various rides and structures were laid out all around us. We were driving past amusement park rides, right next to the car. We parked and started our adventure. I felt like one of those explorers of abandoned places you see on YouTube.

They had an old Whip ride, and we walked up the ramp to get a good look at the ride platform. There was a big fat raccoon walking around. Once he saw us, he scurried into where a floor panel had been removed, his winter den. We strolled around an abandoned park in our winter jackets, past various structures, food stands, game buildings, an arcade, and the flat rides, all in various states of disassembly for the winter. The paratrooper, the roundup, the roll-o-plane. All of these rides that had been at the various parks from my childhood appeared to be brand new, as if they had just come out of the factory. It was incredible.

Throughout all this exploration, off in the distance, I could always see the biggest reason this unexpected visit was so exciting, the famous Phoenix Rollercoaster. The Phoenix is legendary in coaster circles. A wooden double out and back configuration originally built in 1947 as the Rocket at Playland amusement park in San Antonio, Texas. Playland closed in 1980, and it remained SBNO (Standing But No Operating) for a few years until Knoebels, which also owns a lumber business, purchased it. They disassembled the Rocket, transported the pieces from Texas to Elysburg, PA, and reassembled it as The Phoenix. It is always one of the top-rated wooden coasters in the world, so through all of this exploration so far, I knew the big payoff was still to come.

Eventually, we made our way back toward the Phoenix. It is a very long and narrow coaster that stretches across the back of the park. The entire ride was visible because there was a large open area along the entire side of the structure. As the Phoenix came into view, we noticed 2 pickup trucks and some workers on the structure. As we approached, one of the men started to approach us.

“Oh no, we are screwed,” I whispered to Ditty.

“Calm down, Dickles,” he reassured me, “it's not a big deal.”

The man approached. He was a large guy with a grey beard wearing well-worn clothes. “Are you guys with A.C.E?”

Instant relief - A.C.E. was American Coaster Enthusiasts. Of course, I was a member of ACE.

“Yes! This is my first time seeing the phoenix.”

“Would you like a tour?”

This situation was turning into a complete miracle.

We introduced ourselves. Len worked as a roller coaster construction contractor and consultant. Imagine that, a roller coaster consultant! His company was currently doing some track modifications and upgrades to Phoenix over the winter. His son was with him. He told me how they had worked on many wooden roller coasters around the US at various levels of capacity. This was the first time I had even met someone who actually built roller coasters.

Len took us for a full tour around Phoenix. We went under the entire structure. We walked on the Tin Lizzie ‘Olde Fashioned Car’ track that runs under the coaster. We then went up to the station, which was covered in sawhorses, tools, and working equipment. I had been in many coaster stations of my lifetime, but never in this state. It was so cool to get a behind-the-scenes experience. I got to sit in the Phoenix’s control booth. Len showed me what all of the buttons on the control panel did (there were fewer than I expected). We got to see the giant flywheel and mechanism of the chain lift - I think it was called the “lift shed”. There was also a curvy, dark tunnel that the car entered after exiting the station, before it hit the lift hill. We walked through the dark tunnel together, then were brought out into and under the coaster structure.

Len spent an hour with us on that cold December day and took photos with us. It was generous of him. He was truly a coaster lover like me.

Ditty has always been a generous, thoughtful friend. The Knoebels Christmas miracle remains one of the most special gifts he’s given me.